A couple of days ago, one of the many grief-y Instagram accounts I follow posted: “Death anniversary. The shittiest of all anniversaries.” And I went, “well, duh.”

Seeing on it the day before the 15th anniversary of my brother David’s death, I was especially unimpressed with its lack of profundity. But it offered an important kind of permission to me, and others. Because despite the fact that I’ve spent more than a decade now trying to assure myself and others that there’s nothing pathological about still feeling shitty after lots of time has passed after a loss, and that there’s no inappropriate way to grieve, I still spent yesterday with some vague sense I was doing it wrong.

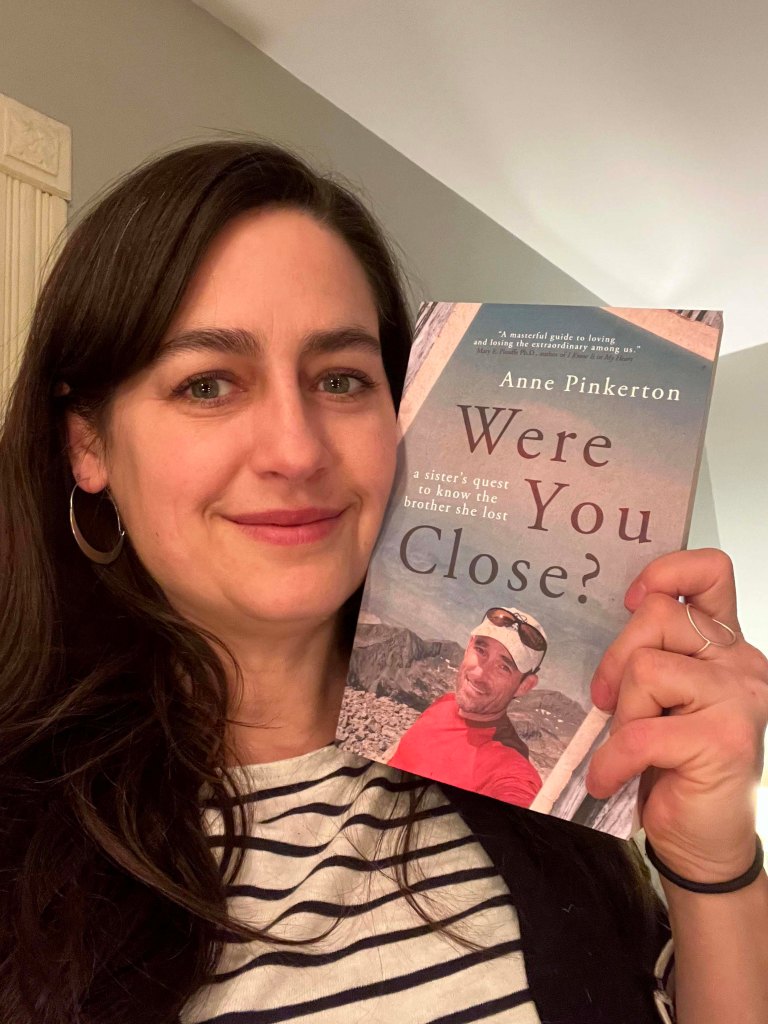

Because it has been fifteen years, after all, but I still felt pretty awful. I’ve written and published several essays and, now, a whole book about sibling loss. I’ve given a dozen readings, talks, and workshops this year, assuring others that they are entitled to their feelings during bereavement, that there is no time limit, how we never really “get over” these things.

Yet whenever I simply looked up at the clear blue sky, the same as the one when I got the call that David had gone missing while hiking in Colorado, tears leaked from the corners of my eyes, and I wondered what was wrong with me. Since I spent the 10th anniversary of David’s death in Colorado, on the mountain where he fell, I sensed I should be in Colorado again, it being a kind of milestone year again. But I wasn’t looking at the majestic Sangre de Christos, facing them, addressing what they took from me, asking myself why I hadn’t planned better.

And then? I tried to distract myself from all of these hard feelings, which is not my usual M.O. at all; I pride myself on directly exploring at the pain of bereavement, believing that working through the experience instead of avoiding it is the only true way to gain control, perspective, and knowledge. But I didn’t want to this time, damn it, and I guess I wasn’t alone.

I called my mom, but neither of us brought up what day it was. Unlike previous years, I didn’t text my surviving brother to tell him I love him, and he didn’t text me. I didn’t see posts from my brother’s friends marking the date. I meant to write this blog post, but didn’t feel like it; instead, I went to a local fair with dear friends. Among the colorful flashing lights of carnival rides and delighted screams of kids, barns full of furry and feathered 4-H farm animals, carts selling a huge variety of fried foods, lines of sunburned people at the beer tent, and the smashing of cars at the demolition derby, I attempted to focus on anything other than my feelings.

It was as different as the the remote and quiet beauty of the San Luis Valley in Southern Colorado as I could possibly imagine. But I sat in the stands watching wheels spinning out in a dirt ring next to my old friend, Caleb, talking about how much his deceased wife, my dear friend Teri, used to love the chaos of this spectacle. When admiring the fancy chickens, I thought about my friend Cate’s silkies with their hilarious poufs of feathers, how much she loves them and how fragile they are; they keep dying on her. I walked by the games — shooting, darts, ring toss — and thought about how David would have won me a prize, playing nothing myself.

But I also made sure to enjoy everything I could, not taking anything for granted after all my losses: I savored crispy onion rings with mustard, cooed at astonishingly tiny baby lambs, reminisced about riding those crazy swings that spin you dizzyingly outward and upward, which I did last year at a fair in Ireland. Most important, I basked in the love of my friends — some of whom I’ve known half my life and all of whom I consider chosen family. I laughed, hugged, cheered, smiled, and cried a little. I appreciated what is while honoring what isn’t anymore — even by going to the fair.

The reality is that death and life are hand-in-hand all the time, in everything. Sure, yesterday provided an amplification due to the nature of marking another year gone by without my handsome, brilliant, generous, accomplished brother. But it’s good to keep in mind. Without the pain, the joy isn’t quite as joyful.

This morning, over coffee, I see this headline in The New York Times: “Anderson Cooper is Still Learning to Live with Loss.” And I say again, “well, duh.” I’ve been madly appreciative of Cooper’s podcast about grief, All There Is, and his writing about the losses of his dad, brother, and mom. With his enormous recognition and abundant respect, his soap box will always be much bigger than mine, his reach on these subjects massive by comparison. I’ve made it a personal mission to talk about the things we don’t talk about culturally. I am so grateful for his willingness to share stories about loss on such a large platform that I sent him a love note and a copy of Were You Close?

In this new article, Cooper acknowledges he would never have gotten into his line of work if not for his formative experiences with loss; there’s a reason why he’s so compassionate even in a war zone. That “doing the work” and coping is hard, but vital. He says, “In terms of acknowledging grief and sadness and allowing myself to be vulnerable, I don’t know exactly how to do that, but that’s what I’m looking to learn. I used to see this sadness behind my mom’s eyes. I want my kids to not see that behind my eyes. I don’t want it to be behind my eyes anymore.”

He allows himself to cry a little. The interviewer, David Marchese, admits he lost his best friend to suicide and what it taught him: “I know I now feel more gratitude and appreciation for life because of that loss.” They discuss Steven Colbert’s acknowledgement that grief is also a gift.

So, on this day-after-the-15th-anniversary-of-losing-David, I am rededicating myself. I accept that it still hurts, but also that I don’t want people to look at me and see sadness behind my eyes. I will keep learning, practicing gratitude, and sharing my stories, recognizing that we will always, always be learning to live with our losses. Well, duh.

Leave a comment